Firstly, I think it’s important to note that with any language you can’t really progress without some sort of interaction with a native speaker. This is because there are certain stresses and sounds in every language that you can only practice in conversation, and pick up from constant dialogue. You also can’t really hear your own accent the same way that a native speaker of that language will be able to – and it’s crucial to gauge how much is being understood by them, after all the purpose of learning any language is communication.

In addition, to add to this dull disclaimer, without spending some serious time sitting down with your books, and learning the basic grammar points, then your writing in a language is unlikely to progress beyond simple words and basic phrases.

So, those are the basic limitations of this post. There’s a reason that schools focus so much on grammar rules and role play, and especially when you’re new to a language, you can’t really afford to neglect either of these. However, here are some ideas for things that you can do if you’re going solo, unable to enroll in classes, or just want some extra tips for improving your reading and listening skills!

I’ve also focused on some less common non-European languages, which British and American students are less likely to have been taught at school, and which are sometimes difficult to find resources for on the most common language learning sites (e.g, Babble).

- Listen to music.

This is even better if you can get hold of a copy of the lyrics in translation! For Hindi songs you’ll be spoilt for choice, especially as virtually every Bollywood film is accompanied by a complete soundtrack. The music videos for such songs are worthy of being cinematography pieces in themselves (see “Dilli Wali Girlfriend”; translation “My girlfriend from Delhi”). For Mandarin, apps like Ting Yinyue (听音乐) are really good for when you’re on the go.

- Read children’s books.

Useful for understanding very simple grammar points and basic sentence construction. Also good because children’s literature tends to avoid too much slang, and if anything it might be slightly old-fashioned vocabulary used, depending on the style of book. For example, I’ve been reading a couple of “Martina” (玛蒂娜)books for young children, and learning words like “Miller” (磨坊主/Mòfāng zhǔ) which are almost archaic in modern Mandarin.

- Watch films and TV in your target language, with or without subtitles, depending on your level!

With the dawn of Youtube, you really can find just about anything you want. On most TVs you’ll also have access to channels in different languages, for example, in the UK we have Rishtey TV and (Hindi). We also have access to CCTV (mainland China news) in Mandarin, if you have a freeview box. Watching something also gives clues as to what is going on if you can’t follow the dialogue! TV and films in another language are important indicators of what a culture cares about, and what those people might be interested in. For example, at the heart of most Indian dramas are the values of family loyalty (vs. personal interests), a desire to succeed (but adhere to society’s boundaries), and a respect for tradition in an increasingly modern world. Meanwhile, Chinese films tend to fixate on the past, or a version of historical events, they often highlight the value of true friendship, and the celebration of perseverance in a turbulent world (e.g., the award-winning film To live, 1994).

- Complete children’s activity books.

This really works because you can reinforce your vocab. knowledge and pick up new words for completing puzzles and games (usually instruction words like “choose” or “circle”). Due to the simple nature of the activities you can usually work out the meaning of anything you’re unfamiliar with, and the tasks themselves are so basic enough that you won’t become frustrated with the activity. Plus they’re usually quite short.

- Read casual magazines.

I picked up some magazines in China which were aimed at teenage girls. As well as introducing me to contemporary slang, it’s also helped me to be familiar with the way that young women in China refer to themselves, and how they perceive themselves in society. I’ve noticed that the magazines that I’ve got tend to be elaborately illustrated in a Japanese manga/anime style, and contain a surprising amount of short, fictional stories, and no sign of western-style horoscopes!

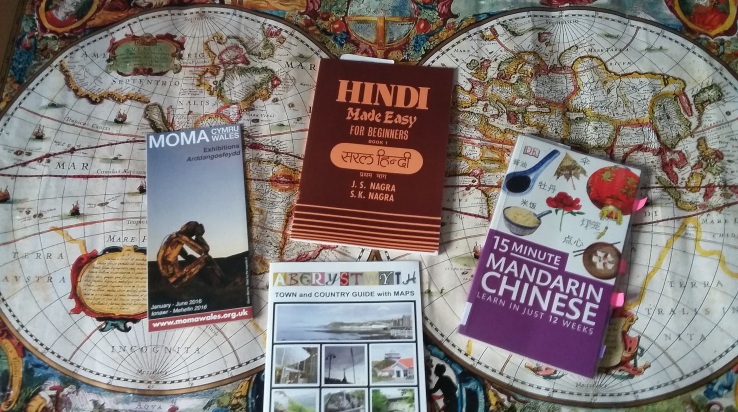

- Make use of apps and online sites.

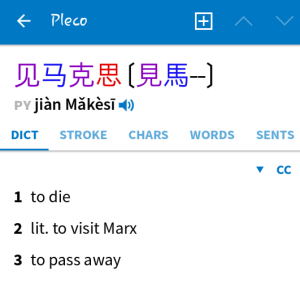

Memrise and Pleco (魚) are my favourites here.

Pleco absolutely dominates the Chinese-for-non-natives scene, and it’s not hard to see why. The basic package comes with a built-in dictionary, pronunciation features, and a pinyin and character look-up. For a small sum, you can get some amazing add-ons, like a “stroke order” feature, which I have, to teach you the correct way to write unfamiliar characters. Pleco is amazing because it constantly updates itself with the latest dictionary entries (e.g, you can find out Donald Trump’s Chinese name…) and it also cross-references to phenomena in Chinese culture, including historical works of literature, the names of celebrities and famous films.

Memrise is incredible because of the sheer diversity of its user-generated courses. The downside if that it’s not really accessible if you’re offline – unless you pay. However, for those graced with Wifi, it’s a gift. Though it is very vocabulary-heavy, it’s helped me to learn loads of phrases in Hindi, Mandarin and Burmese, and it was especially helpfully for learning Devanagari script (for Hindi) and the Burmese alphabet. The courses that you click through focus on repetition and using images to associate words with their meanings, or to recall their pronunciation. Associative learning is the key principle here, and for people who like to learn visually (though the best courses also have audio content) then it’s extremely engaging. Games and leaderboards encourage healthy competition, not to mention the constant reminders and timed emails you can set up to force you to complete a daily goal for your language practice!

- Start an audio course, or download some podcasts.

Podcasts are another invaluable tool. Language learning in the 21st century has been transformed by the internet, and this has certainly improved access to all kinds of resources. For Mandarin I tend to have quite simple podcasts, which basically just run through basic phrases and vocabulary, but for Hindi I really like the “Namaste Dosti” series, which is targeted at beginners and talks you through a variety of different dialogues. This series focuses on what you might need to get around in India, and does a good job of simulating market scenes etc.

Audio has been my main method of instruction for Burmese, a language so unstudied that other resources seem scarce. SOAS (School of African and Oriental Studies, a university based in London) has produced a brilliant “Burmese By Ear” (BBE) course, free to download, which includes dozens of audio clips, structured into lessons, with an accompanying pdf booklet for reference. At points, notes on pronunciation can get quite technical (“aspirated consonants” and “plain ps” abound), but overall this is a great resource, covering “survival” phrases, numbers, and a surprising number of cultural insights.

[…] more than breadth. This is especially true when learning a language, as I used to constantly balance learning Mandarin with whatever else was going on at the time, Bangla, Vietnamese etc. Now I can really see the […]

LikeLike

[…] The inspiration for this post actually came from a Chinese concept, the idea that a landscape is essentially composed of two unique (but united) elements, rivers and mountains. The Mandarin word for “landscape” is literally “mountain/water” (山水). Ever since studying Mandarin Chinese in Jinan, Shandong province, two years ago, I’ve endeavoured to keep learning and keep practicing my 普通话 ! […]

LikeLike

[…] traditions in the world, Mandarin Chinese makes use of hundreds of idioms. When I get stuck with my own language learning, I often turn to idioms as a way of getting things moving again, as they can usually be equated […]

LikeLike